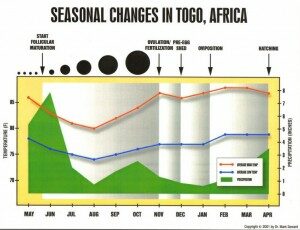

For this addition to ball python breeding section, I’d to talk about follicular development and how I cycle my animals to prepare them for the breeding season. Now when I say “cycle” I’m referring to how I manipulate the temperatures to simulate the changes of the seasons which signal the animals that it’s time for breeding.

Property of Doc Seward @ www.ballbreeding.com

The goal is to simulate the changing of seasons as close as possible to that of their native climate in Africa. I often hear breeders talk about breeding their ball pythons with no temperature cycling at all and yes, it can be done with no temperature cycling. That being said, if you’re like me and looking to have the highest amount of success possible, then yes, cycling those temps is essential. Just like I talked about in a previous article, anybody can put two snakes in a box and get eggs, but we’re not looking to just produce “some” clutches, heck no, we’re looking for maximum production which does take experience and know how.

Cycling those temps serves several different purposes to ball pythons in regards to reproduction, but the one purpose we’re most concerned about is follicular development. Basically, follicles are under developed, unfertilized, immature ova which turn into eggs later in the season if all goes as planned. We as breeders have learned that mature female ball pythons tend to respond to the change in seasons by developing follicles as well as letting off various hormones that work wonders to stimulate breeder males.

Follicular development follows right along with the changing of the seasons and growth rates are further stimulated with exposure to falling temps as well as exposure to rising temperatures. Ball pythons start developing follicles and copulating with males in the cooler months of the year. That follicular growth progresses through these cooler months as the animals build towards ovulation which is the process of fertilization. With that, it’s important to provide your animals with the proper temps during these months in order for the follicles to fully mature with ovulation eventually taking place and the follicles becoming fertilized eggs.

I had a conversation with 30year reptile breeding veteran Dave Barker once regarding this very topic and Dave said, he believes a lot of the problems with breeders producing slugs in their captive breeding programs is directly related to the animal ovulating prematurely, therefore not fertilizing the follicles at all or only fertilizing a few. I’ve observed this in my own personal collection when I raised the temps too quickly, too early in the season. In my personal opinion I believe the rise in temperature sends a signal to the female that the breeding season is coming to an end and she’d better ovulate or else the stored sperm may not survive the heat of the summer. That thinking in mind, she ovulates prematurely hoping to save any shot at reproduction for the year. I may be way off there, but I really believe this to be the reasoning behind it.

We combat premature ovulation by maintaining a cooler temperature which is followed by a gradually rise back to off season temps as the season is coming to an end. A few years back I had a horrible breeding season that resulted in about 50-60% of my production being slugs. That year I ran my overall temps much higher and didn’t bother to cycle my animals for the breeding season and although it cost me financially, I did gain a lot of knowledge from the experience. The following year I adopted the cycling plan I still use to this day and I’ve experienced terrific results, my yearly slug count is in single digits and actually this season (2012) I believe I haven’t had a single slug.

To start I keep my hot spot temperature much lower year round down from the mid 90’s to right around 86 degrees. Some days it’ll be a little higher some days a little lower, but right around the 86 degree mark has worked really for me. Starting in late October I start dropping my nightly temps by 2 degrees a week for 3 weeks. That’s only a 6 degree adjustment over the course of 3 weeks, but it works wonders as my ambient room temps are also naturally changing with the season. During the off season my snakes receive a 86 degree hot spot 24/7 and the ambient room heat can peak out in the high 80’s as well. Now as the season changes my ambient room temperature will fall down to the low 70’s so combine that with the 6 degree night drop and you’ve got a pretty significant season change.

To start I keep my hot spot temperature much lower year round down from the mid 90’s to right around 86 degrees. Some days it’ll be a little higher some days a little lower, but right around the 86 degree mark has worked really for me. Starting in late October I start dropping my nightly temps by 2 degrees a week for 3 weeks. That’s only a 6 degree adjustment over the course of 3 weeks, but it works wonders as my ambient room temps are also naturally changing with the season. During the off season my snakes receive a 86 degree hot spot 24/7 and the ambient room heat can peak out in the high 80’s as well. Now as the season changes my ambient room temperature will fall down to the low 70’s so combine that with the 6 degree night drop and you’ve got a pretty significant season change.

I’ll maintain these breeding season temperatures until the season begins to naturally change once again which is usually around April or May at which point I’ll rise the temps back up in 2 degree increments for 3 weeks. This step is absolutely critical because the last thing you want is a sudden increase in temps knowing that it’ll likely cause your females to ovulate prematurely.

Taking all of what I just said into consideration, what I do in my little microenvironment may or may not work for you. Only through trial and error will you be able to dial in what works best in your environment, but having the “know how” will most certainly speed up that learning curb. If you have any questions I’ll gladly help you out as much as possible just post them on the question and answer page.